Kernel API¶

Lab objectives¶

- Familiarize yourself with the basic Linux kernel API

- Description of memory allocation mechanisms

- Description of locking mechanisms

Overview¶

Inside the current lab we present a set of concepts and basic functions required for starting Linux kernel programming. It is important to note that kernel programming differs greatly from user space programming. The kernel is a stand-alone entity that can not use libraries in user-space (not even libc). As a result, the usual user-space functions (printf, malloc, free, open, read, write, memcpy, strcpy, etc.) can no longer be used. In conclusion, kernel programming is based on a totally new and independent API that is unrelated to the user-space API, whether we refer to POSIX or ANSI C (standard C language library functions).

Accessing memory¶

An important difference in kernel programming is how to access and allocate memory. Due to the fact that kernel programming is very close to the physical machine, there are important rules for memory management. First, it works with several types of memory:

- Physical memory

- Virtual memory from the kernel address space

- Virtual memory from a process’s address space

- Resident memory - we know for sure that the accessed pages are present in physical memory

Virtual memory in a process’s address space can not be considered resident due to the virtual memory mechanisms implemented by the operating system: pages may be swapped or simply may not be present in physical memory as a result of the demand paging mechanism. The memory in the kernel address space can be resident or not. Both the data and code segments of a module and the kernel stack of a process are resident. Dynamic memory may or may not be resident, depending on how it is allocated.

When working with resident memory, things are simple: memory can be accessed at any time. But if working with non-resident memory, then it can only be accessed from certain contexts. Non-resident memory can only be accessed from the process context. Accessing non-resident memory from the context of an interrupt has unpredictable results and, therefore, when the operating system detects such access, it will take drastic measures: blocking or resetting the system to prevent serious corruption.

The virtual memory of a process can not be accessed directly from the kernel. In general, it is totally discouraged to access the address space of a process, but there are situations where a device driver needs to do it. The typical case is where the device driver needs to access a buffer from the user-space. In this case, the device driver must use special features and not directly access the buffer. This is necessary to prevent access to invalid memory areas.

Another difference from the user-space scheduling, relative to memory, is due to the stack, a stack whose size is fixed and limited. A stack of 4K it is used in Linux, and a stack of 12K is used in Windows. For this reason, the allocation of large structures on stack or the use of recursive calls should be avoided.

Contexts of execution¶

In relation to kernel execution, we distinguish two contexts: process context and interrupt context. We are in the process context when we run code as a result of a system call or when we run in the context of a kernel thread. When we run in a routine to handle an interrupt or a deferrable action, we run in an interrupt context.

Some of the kernel API calls can block the current process. Common examples are

using a semaphore or waiting for a condition. In this case, the process is

put into the WAITING state and another process is running. An interesting

situation occurs when a function that can lead to the current process to be

suspended, is called from an interrupt context. In this case, there is no

current process, and therefore the results are unpredictable. Whenever the

operating system detects this condition will generate an error condition that

will cause the operating system to shut down.

Locking¶

One of the most important features of kernel programming is parallelism. Linux supports SMP systems with multiple processors and kernel preemptivity. This makes kernel programming more difficult because access to global variables must be synchronized with either spinlock primitives or blocking primitives. Although it is recommended to use blocking primitives, they can not be used in an interrupt context, so the only locking solution in the context of an interrupt is spinlocks.

Spinlocks are used in order to achieve mutual exclusion. When it can not get

access to the critical region, it does not suspend the current process, but it

uses the busy-waiting mechanism (waiting in a while() loop for the lock

to be released).

The code that runs in the critical region protected by a spinlock is not allowed

to suspend the current process (it must adhere to the execution conditions in

the interrupt context). Moreover, the CPU will not be released except for

the case of an interrupt. Due to the mechanism used, it is important that a

spinlock is being held as little time as possible.

Preemptivity¶

Linux uses preemptive kernels. The notion of preemptive multitasking should not be confused with the notion of a preemptive kernel. The notion of preemptive multitasking refers to the fact that the operating system forcefully interrupts a process running in user space when its quantum (time slice) expires, in order to run another process. A kernel is preemptive if a process running in kernel mode (as a result of a system call) can be interrupted so that another process is being run.

Because of preemptivity, when we share resources between two portions of code that can run from different process contexts, we need to protect ourselves with synchronization primitives, even in the case of a single processor.

Linux Kernel API¶

Convention indicating errors¶

For Linux kernel programming, the convention used for calling functions to indicate success is the same as in UNIX programming: 0 for success, or a value other than 0 for failure. For failures, negative values are returned as shown in the example below:

if (alloc_memory() != 0)

return -ENOMEM;

if (user_parameter_valid() != 0)

return -EINVAL;

The exhaustive list of errors and a summary explanation can be found in

include/asm-generic/errno-base.h and in

includes/asm-generic/ernno.h.

Strings of characters¶

In Linux, the kernel programmer is provided with the usual routine functions:

strcpy(), strncpy(), strlcpy(), strcat(),

strncat(), strlcat(), strcmp(), strncmp(),

strnicmp(), strchr(), strnchr(), strrchr(),

strstr(), strlen(), memset(), memmove(),

memcmp(), etc. These functions are declared in the

include/linux/string.h header and are implemented in the kernel in the

lib/string.c file.

printk¶

The printf equivalent in the kernel is printk, defined in

include/linux/printk.h. The printk() syntax is very similar

to printf(). The first

parameter of printk() decides the log category in which the current log

falls into:

#define KERN_EMERG "<0>" /* system is unusable */

#define KERN_ALERT "<1>" /* action must be taken immediately */

#define KERN_CRIT "<2>" /* critical conditions */

#define KERN_ERR "<3>" /* error conditions */

#define KERN_WARNING "<4>" /* warning conditions */

#define KERN_NOTICE "<5>" /* normal but significant condition */

#define KERN_INFO "<6>" /* informational */

#define KERN_DEBUG "<7>" /* debug-level messages */

Thus, a warning message in the kernel would be sent with:

printk(KERN_WARNING "my_module input string %s\n", buff);

If the logging level is missing from the printk() call, logging is done

with the default level at the time of the call. One thing to keep in mind is

that messages sent with printk() are only visible on the console if and

only if their level exceeds the default level set on the console.

To reduce the size of lines when using printk(), it is recommended to

use the following help functions instead of directly using the printk()

call:

pr_emerg(fmt, ...); /* similar to printk(KERN_EMERG pr_fmt(fmt), ...); */

pr_alert(fmt, ...); /* similar to printk(KERN_ALERT pr_fmt(fmt), ...); */

pr_crit(fmt, ...); /* similar to printk(KERN_CRIT pr_fmt(fmt), ...); */

pr_err(fmt, ...); /* similar to printk(KERN_ERR pr_fmt(fmt), ...); */

pr_warning(fmt, ...); /* similar to printk(KERN_WARNING pr_fmt(fmt), ...); */

pr_warn(fmt, ...); /* similar to cu printk(KERN_WARNING pr_fmt(fmt), ...); */

pr_notice(fmt, ...); /* similar to printk(KERN_NOTICE pr_fmt(fmt), ...); */

pr_info(fmt, ...); /* similar to printk(KERN_INFO pr_fmt(fmt), ...); */

A special case is pr_debug() that calls the printk() function

only when the DEBUG macro is defined or if dynamic debugging is used.

Memory allocation¶

In Linux only resident memory can be allocated, using kmalloc() call.

A typical kmalloc() call is presented below:

#include <linux/slab.h>

string = kmalloc (string_len + 1, GFP_KERNEL);

if (!string) {

//report error: -ENOMEM;

}

As you can see, the first parameter indicates the size in bytes of the allocated

area. The function returns a pointer to a memory area that can be directly used

in the kernel, or NULL if memory could not be allocated. The second

parameter specifies how allocation should be done and the most commonly used

values for this are:

GFP_KERNEL- using this value may cause the current process to be suspended. Thus, it can not be used in the interrupt context.GFP_ATOMIC- using this value it ensures that thekmalloc()function does not suspend the current process. It can be used anytime.

The counterpart to the kmalloc() function is kfree(), a function

that receives as argument an area allocated by kmalloc(). This function

does not suspend the current process and can therefore be called from any

context.

lists¶

Because linked lists are often used, the Linux kernel API provides a unified

way of defining and using lists. This involves using a

struct list_head element in the structure we want to consider as a

list node. The struct list_head is defined in

include/linux/list.h along with all the other functions that manipulate

the lists. The following code shows the definition of

the struct list_head and the use of an element of this type in another

well-known structure in the Linux kernel:

struct list_head {

struct list_head *next, *prev;

};

struct task_struct {

...

struct list_head children;

...

};

The usual routines for working with lists are the following:

LIST_HEAD(name)is used to declare the sentinel of a listINIT_LIST_HEAD(struct list_head *list)()is used to initialize the sentinel of a list when dynamic allocation is made, by setting the value of thenextandprevto list fields.list_add(struct list_head *new, struct list_head *head)()adds thenewelement after theheadelement.list_del(struct list_head *entry)()deletes the item at theentryaddress of the list it belongs to.list_entry(ptr, type, member)returns the structure with the typetypethat contains the elementptrfrom the list, having the namememberwithin the structure.list_for_each(pos, head)iterates over a list usingposas a cursor.list_for_each_safe(pos, n, head)iterates over a list usingposas a cursor andnas a temporary cursor. This macro is used to delete an item from the list.

The following code shows how to use these routines:

#include <linux/slab.h>

#include <linux/list.h>

struct pid_list {

pid_t pid;

struct list_head list;

};

LIST_HEAD(my_list);

static int add_pid(pid_t pid)

{

struct pid_list *ple = kmalloc(sizeof *ple, GFP_KERNEL);

if (!ple)

return -ENOMEM;

ple->pid = pid;

list_add(&ple->list, &my_list);

return 0;

}

static int del_pid(pid_t pid)

{

struct list_head *i, *tmp;

struct pid_list *ple;

list_for_each_safe(i, tmp, &my_list) {

ple = list_entry(i, struct pid_list, list);

if (ple->pid == pid) {

list_del(i);

kfree(ple);

return 0;

}

}

return -EINVAL;

}

static void destroy_list(void)

{

struct list_head *i, *n;

struct pid_list *ple;

list_for_each_safe(i, n, &my_list) {

ple = list_entry(i, struct pid_list, list);

list_del(i);

kfree(ple);

}

}

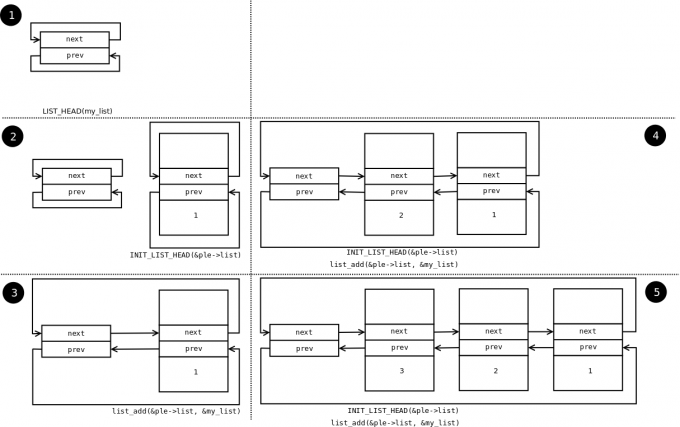

The evolution of the list can be seen in the following figure:

You see the stack type behavior introduced by the list_add macro,

and the use of a sentinel.

From the above example, it can be noticed that the way to define and use a list

(double-linked) is generic and, at the same time, it does not introduce an

additional overhead. The struct list_head is used to maintain the

links between the list elements. It can be noticed that iterating over the list

is also done with this structure, and that retrieving a list element can be done

using list_entry. This idea of implementing and using a list is not

new, as it has already been described in The Art of Computer Programming by

Donald Knuth in the 1980s.

Several kernel list functions and macro definitions are presented and explained

in the include/linux/list.h header.

Spinlock¶

spinlock_t (defined in linux/spinlock.h) is the basic type

that implements the spinlock concept in Linux. It describes a spinlock, and the

operations associated with a spinlock are spin_lock_init(),

spin_lock(), spin_unlock(). An example of use is given below:

#include <linux/spinlock.h>

DEFINE_SPINLOCK(lock1);

spinlock_t lock2;

spin_lock_init(&lock2);

spin_lock(&lock1);

/* critical region */

spin_unlock(&lock1);

spin_lock(&lock2);

/* critical region */

spin_unlock(&lock2);

In Linux, you can use reader-writer spinlocks, useful for readers-writers

problems.

These types of locks are identified by rwlock_t, and the functions

that can work on a reader-writer spinlock are:

* rwlock_init()

* read_lock()

* write_lock()

An example of use:

#include <linux/spinlock.h>

DEFINE_RWLOCK(lock);

struct pid_list {

pid_t pid;

struct list_head list;

};

int have_pid(struct list_head *lh, int pid)

{

struct list_head *i;

void *elem;

read_lock(&lock);

list_for_each(i, lh) {

struct pid_list *pl = list_entry(i, struct pid_list, list);

if (pl->pid == pid) {

read_unlock(&lock);

return 1;

}

}

read_unlock(&lock);

return 0;

}

void add_pid(struct list_head *lh, struct pid_list *pl)

{

write_lock(&lock);

list_add(&pl->list, lh);

write_unlock(&lock);

}

mutex¶

A mutex is a variable of the struct mutex type (defined in

linux/mutex.h).

Functions and macros for working with mutexes are listed below:

#include <linux/mutex.h>

/* functions for mutex initialization */

void mutex_init(struct mutex *mutex);

DEFINE_MUTEX(name);

/* functions for mutex acquire */

void mutex_lock(struct mutex *mutex);

/* functions for mutex release */

void mutex_unlock(struct mutex *mutex);

Operations are similar to classic mutex operations in user-space or spinlock operations: the mutex is acquired before entering the critical region and it is released after exiting the critical region. Unlike spinlocks, these operations can only be used in process context.

Atomic variables¶

Often, you only need to synchronize access to a simple variable, such as a

counter. For this, an atomic_t type can be used (defined in

include/linux/atomic.h), that holds an integer value. Below are some

operations that can be performed on an atomic_t variable.

#include <asm/atomic.h>

void atomic_set(atomic_t *v, int i);

int atomic_read(atomic_t *v);

void atomic_add(int i, atomic_t *v);

void atomic_sub(int i, atomic_t *v);

void atomic_inc(atomic_t *v);

void atomic_dec(atomic_t *v);

int atomic_inc_and_test(atomic_t *v);

int atomic_dec_and_test(atomic_t *v);

int atomic_cmpxchg(atomic_t *v, int old, int new);

Use of atomic variables¶

A common way of using atomic variables is to store the status of an action (e.g. a flag). So we can use an atomic variable to mark exclusive actions. For example, we consider that an atomic variable can have the LOCKED and UNLOCKED values, and if the respective variable equals LOCKED then a specific function should return -EBUSY. Such an usage is shown schematically in the code below:

#define LOCKED 0

#define UNLOCKED 1

static atomic_t flag;

static int my_acquire(void)

{

int initial_flag;

/*

* Check if flag is UNLOCKED; if not, lock it and do it atomically.

*

* This is the atomic equivalent of

* if (flag == UNLOCKED)

* flag = LOCKED;

* else

* return -EBUSY;

*/

initial_flag = atomic_cmpxchg(&flag, UNLOCKED, LOCKED);

if (initial_flag == LOCKED) {

printk(KERN_ALERT "Already locked.\n");

return -EBUSY;

}

/* Do your thing after getting the lock. */

[...]

}

static void my_release(void)

{

/* Release flag; mark it as unlocked. */

atomic_set(&flag, UNLOCKED);

}

void my_init(void)

{

[...]

/* Atomic variable is initially unlocked. */

atomic_set(&flag, UNLOCKED);

[...]

}

The above code is the equivalent of using a trylock (such as

pthread_mutex_trylock()).

We can also use a variable to store the size of a buffer and for atomic updates of the respective variable. The code below is such an example:

static unsigned char buffer[MAX_SIZE];

static atomic_t size;

static void add_to_buffer(unsigned char value)

{

buffer[atomic_read(&size)] = value;

atomic_inc(&size);

}

static unsigned char remove_from_buffer(void)

{

unsigned char value;

value = buffer[atomic_read(&size)];

atomic_dec(&size);

return value

}

static void reset_buffer(void)

{

atomic_set(&size, 0);

}

void my_init(void)

{

[...]

/* Initialized buffer and size. */

atomic_set(&size, 0);

memset(buffer, 0, sizeof(buffer));

[...]

}

Atomic bitwise operations¶

The kernel provides a set of functions (in asm/bitops.h) that modify or

test bits in an atomic way.

#include <asm/bitops.h>

void set_bit(int nr, void *addr);

void clear_bit(int nr, void *addr);

void change_bit(int nr, void *addr);

int test_and_set_bit(int nr, void *addr);

int test_and_clear_bit(int nr, void *addr);

int test_and_change_bit(int nr, void *addr);

Addr represents the address of the memory area whose bits are being

modified or tested and nr is the bit on which the operation is

performed.

Exercises¶

Important

To solve exercises, you need to perform these steps:

- prepare skeletons from templates

- build modules

- copy modules to the VM

- start the VM and test the module in the VM.

The current lab name is kernel_api. See the exercises for the task name.

The skeleton code is generated from full source examples located in

tools/labs/templates. To solve the tasks, start by generating

the skeleton code for a complete lab:

tools/labs $ make clean

tools/labs $ LABS=<lab name> make skels

You can also generate the skeleton for a single task, using

tools/labs $ LABS=<lab name>/<task name> make skels

Once the skeleton drivers are generated, build the source:

tools/labs $ make build

Then, copy the modules and start the VM:

tools/labs $ make copy

tools/labs $ make boot

The modules are placed in /home/root/skels/kernel_api/<task_name>.

Alternatively, we can copy files via scp, in order to avoid restarting the VM. For additional details about connecting to the VM via the network, please check Connecting to the VM.

Review the Exercises section for more detailed information.

Warning

Before starting the exercises or generating the skeletons, please run git pull inside the Linux repo, to make sure you have the latest version of the exercises.

If you have local changes, the pull command will fail. Check for local changes using git status.

If you want to keep them, run git stash before pull and git stash pop after.

To discard the changes, run git reset --hard master.

If you already generated the skeleton before git pull you will need to generate it again.

0. Intro¶

Using LXR find the definitions of the following symbols in the Linux kernel:

struct list_headINIT_LIST_HEAD()list_add()list_for_eachlist_entrycontainer_ofoffsetof

1. Memory allocation in Linux kernel¶

Generate the skeleton for the task named 1-mem and browse the

contents of the mem.c file. Observe the use of kmalloc()

call for memory allocation.

- Compile the source code and load the

mem.komodule using insmod.- View the kernel messages using the dmesg command.

- Unload the kernel module using the rmmod mem command.

Note

Review the Memory Allocation section in the lab.

2. Sleeping in atomic context¶

Generate the skeleton for the task named 2-sched-spin and browse

the contents of the sched-spin.c file.

- Compile the source code and load the module, according the above info: (make build and make copy)

- Notice that it is waiting for 5 seconds until the insertion order is complete.

- Unload the kernel module.

- Look for the lines marked with:

TODO 0to create an atomic section. Re-compile the source code and reload the module into the kernel.

You should now get an error. Look at the stack trace. What is the cause of the error?

Hint

In the error message, follow the line containing the BUG

for a description of the error. You are not allowed to sleep in

atomic context. The atomic context is given by a section

between a lock operation and an unlock on a spinlock.

Note

The

schedule_timeout() function, corroborated with the

set_current_state macro, forces the current process to wait

for 5 seconds.

Note

Review the Contexts of execution, Locking and Spinlock sections.

3. Working with kernel memory¶

Generate the skeleton for the task named 3-memory directory and

browse the contents of the memory.c file. Notice the comments

marked with TODO. You must allocate 4 structures of type struct

task_info and initialize them (in memory_init()), then print and

free them (in memory_exit()).

(TODO 1) Allocate memory for

struct task_infostructure and initialize its fields:

- The

pidfield to the PID transmitted as a parameter;- The

timestampfield to the value of thejiffiesvariable, which holds the number of ticks that have occurred since the system booted.(TODO 2) Allocate

struct task_infofor the current process, the parent process, the next process, the next process of the next process, with the following information:

- PID of the current process, which can be retrieved from

struct task_structstructure, returned bycurrentmacro.Hint

Search for

pidintask_struct.

- PID of the parent process of the current process.

Hint

Search for the relevant field from

struct task_structstructure. Look after “parent”.

- PID of the next process from the list of processes, relative to the current process.

Hint

Use

next_taskmacro, which returns a pointer to the next process (i.e astruct task_structstructure).

- PID of the next process of the next process, relative to the current process.

Hint

Call the

next_taskmacro 2 times.(TODO 3) Display the four structures.

- Use

printk()to display their two fields:

pidandtimestamp.(TODO 4) Release the memory occupied by the structures (use

kfree()).

Hint

- You can access the current process using

currentmacro. - Look for the relevant fields in the

struct task_structstructure (pid,parent). - Use the

next_taskmacro. The macro returns the pointer to the next process (ie. astruct task_struct*structure).

Note

The struct task_struct structure contains two fields to

designate the parent of a task:

real_parentpoints to the process that created the task or to process with pid 1 (init) if the parent completed its execution.parentindicates to the current task parent (the process that will be reported if the task completes execution).

In general, the values of the two fields are the same, but

there are situations where they differ, for example when

using the ptrace() system call.

Hint

Review the Memory allocation section in the lab.

4. Working with kernel lists¶

Generate the skeleton for the task named 4-list. Browse the

contents of the list.c file and notice the comments marked with

TODO. The current process will add the four structures from the

previous exercise into a list. The list will be built in the

task_info_add_for_current() function which is called when module is

loaded. The list will be printed and deleted in the list_exit()

function and the task_info_purge_list() function.

- (TODO 1) Complete the

task_info_add_to_list()function to allocate astruct task_infostructure and add it to the list.- (TODO 2) Complete the

task_info_purge_list()function to delete all the elements in the list.- Compile the kernel module. Load and unload the module by following the messages displayed by the kernel.

Hint

Review the labs Lists section. When deleting items from

the list, you will need to use either the

list_for_each_safe or list_for_each_entry_safe

macros.

5. Working with kernel lists for process handling¶

Generate the skeleton for the task named 5-list-full. Browse the

contents of the list-full.c and notice comments marked with

TODO. In addition to the 4-list functionality we add the

following:

A

countfield showing how many times a process has been “added” to the list.If a process is “added” several times, no new entry is created in the list, but:

- Update the

timestampfield.- Increment

count.To implement the counter facility, add a

task_info_find_pid()function that searches for a pid in the existing list.If found, return the reference to the

task_infostruct. If not, returnNULL.An expiration facility. If a process was added more than 3 seconds ago and if it does not have a

countgreater than 5 then it is considered expired and is removed from the list.The expiration facility is already implemented in the

task_info_remove_expired()function.

(TODO 1) Implement the

task_info_find_pid()function.(TODO 2) Change a field of an item in the list so it does not expire. It must not satisfy a part of the expiration condition from

task_info_remove_expired().Hint

For

TODO 2, extract the first element from the list (the one referred byhead.next) and set thecountfield to a large enough value. Useatomic_set()function.Compile, copy, load and unload the kernel module following the displayed messages. Kernel module loading will take some time, because

sleep()is being called byschedule_timeout()function.

6. Synchronizing list work¶

Generate the skeleton for the task named 6-list-sync.

- Browse the code and look for

TODO 1string.- Use a spinlock or a read-write lock to synchronize access to the list.

- Compile, load and unload the kernel module.

Important

Always lock data, not code!

Note

Read Spinlock section of the lab.

7. Test module calling in our list module¶

Generate the skeleton for the task named 7-list-test and browse

the contents of the list-test.c file. We’ll use it as a test

module. It will call functions exported by the 6-list-sync

task. The exported functions are the ones marked with extern in

list-test.c file.

To export the above functions from the module located at 6-list-sync/

directory, the following steps are required:

- Functions must not be static.

- Use the

EXPORT_SYMBOLmacro to export the kernel symbols. For example:EXPORT_SYMBOL(task_info_remove_expired);. The macro must be used for each function after the function is defined. Browse the code and look for theTODO 2string in thelist-sync.c.- Remove from the module from 6-list-sync the code that avoids the expiration of a list item (it is in contradiction to our exercise).

- Compile and load the module from

6-list-sync/. Once loaded, it exposes exported functions and can be used by the test module. You can check this by searching for the function names in/proc/kallsymsbefore and after loading the module.- Compile the test module and then load it.

- Use lsmod to check that the two modules have been loaded. What do you notice?

- Unload the kernel test module.

What should be the unload order of the two modules (the module from 6-list-sync and the test module)? What happens if you use another order?