Introduction¶

Lecture objectives:¶

- Basic operating systems terms and concepts

- Overview of the Linux kernel

Basic operating systems terms and concepts¶

User vs Kernel¶

Kernel and user are two terms that are often used in operating systems. Their definition is pretty straight forward: The kernel is the part of the operating system that runs with higher privileges while user (space) usually means by applications running with low privileges.

However these terms are heavily overloaded and might have very specific meanings in some contexts.

User mode and kernel mode are terms that may refer specifically to the processor execution mode. Code that runs in kernel mode can fully [1] control the CPU while code that runs in user mode has certain limitations. For example, local CPU interrupts can only be disabled or enable while running in kernel mode. If such an operation is attempted while running in user mode an exception will be generated and the kernel will take over to handle it.

| [1] | some processors may have even higher privileges than kernel mode, e.g. a hypervisor mode, that is only accessible to code running in a hypervisor (virtual machine monitor) |

User space and kernel space may refer specifically to memory protection or to virtual address spaces associated with either the kernel or user applications.

Grossly simplifying, the kernel space is the memory area that is reserved to the kernel while user space is the memory area reserved to a particular user process. The kernel space is accessed protected so that user applications can not access it directly, while user space can be directly accessed from code running in kernel mode.

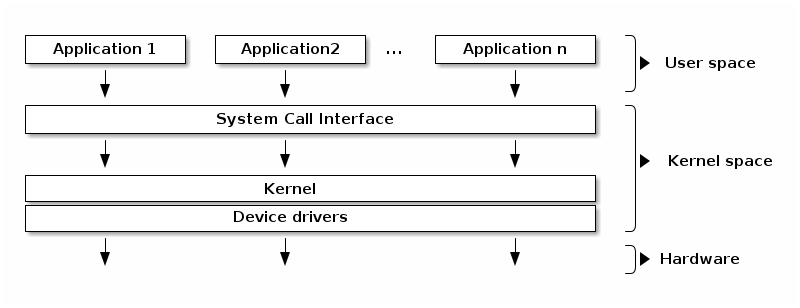

Typical operating system architecture¶

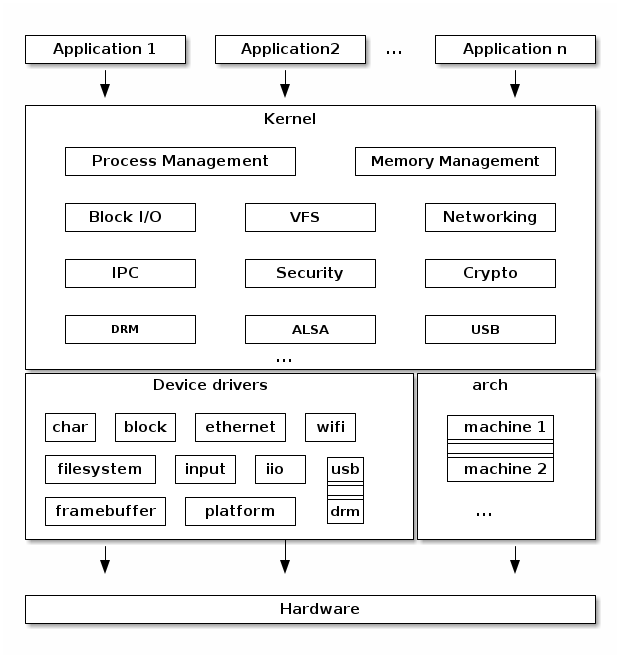

In the typical operating system architecture (see the figure below) the operating system kernel is responsible for access and sharing the hardware in a secure and fair manner with multiple applications.

The kernel offers a set of APIs that applications issue which are generally referred to as “System Calls”. These APIs are different from regular library APIs because they are the boundary at which the execution mode switch from user mode to kernel mode.

In order to provide application compatibility, system calls are rarely changed. Linux particularly enforces this (as opposed to in kernel APIs that can change as needed).

The kernel code itself can be logically separated in core kernel code and device drivers code. Device drivers code is responsible of accessing particular devices while the core kernel code is generic. The core kernel can be further divided into multiple logical subsystems (e.g. file access, networking, process management, etc.)

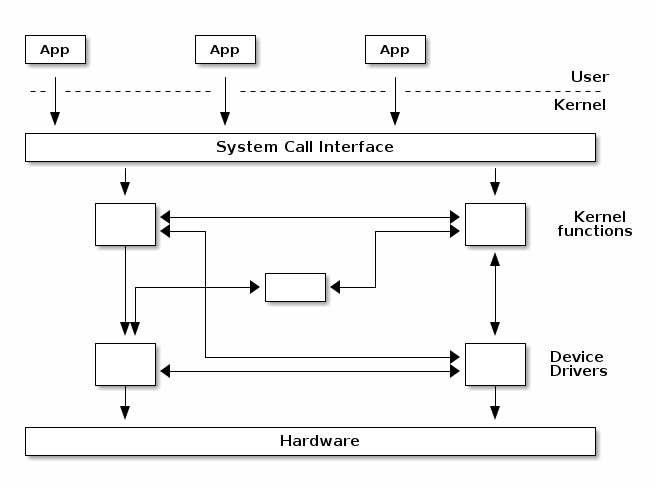

Monolithic kernel¶

A monolithic kernel is one where there is no access protection between the various kernel subsystems and where public functions can be directly called between various subsystems.

However, most monolithic kernels do enforce a logical separation between subsystems especially between the core kernel and device drivers with relatively strict APIs (but not necessarily fixed in stone) that must be used to access services offered by one subsystem or device drivers. This, of course, depends on the particular kernel implementation and the kernel’s architecture.

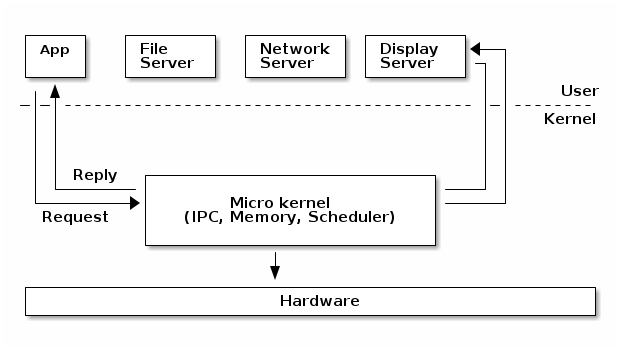

Micro kernel¶

A micro-kernel is one where large parts of the kernel are protected from each-other, usually running as services in user space. Because significant parts of the kernel are now running in user mode, the remaining code that runs in kernel mode is significantly smaller, hence micro-kernel term.

In a micro-kernel architecture the kernel contains just enough code that allows for message passing between different running processes. Practically that means implement the scheduler and an IPC mechanism in the kernel, as well as basic memory management to setup the protection between applications and services.

One of the advantages of this architecture is that the services are isolated and hence bugs in one service won’t impact other services.

As such, if a service crashes we can just restart it without affecting the whole system. However, in practice this is difficult to achieve since restarting a service may affect all applications that depend on that service (e.g. if the file server crashes all applications with opened file descriptors would encounter errors when accessing them).

This architecture imposes a modular approach to the kernel and offers memory protection between services but at a cost of performance. What is a simple function call between two services on monolithic kernels now requires going through IPC and scheduling which will incur a performance penalty [2].

| [2] | https://lwn.net/Articles/220255/ |

Micro-kernels vs monolithic kernels¶

Advocates of micro-kernels often suggest that micro-kernel are superior because of the modular design a micro-kernel enforces. However, monolithic kernels can also be modular and there are several approaches that modern monolithic kernels use toward this goal:

- Components can enabled or disabled at compile time

- Support of loadable kernel modules (at runtime)

- Organize the kernel in logical, independent subsystems

- Strict interfaces but with low performance overhead: macros, inline functions, function pointers

There is a class of operating systems that (used to) claim to be hybrid kernels, in between monolithic and micro-kernels (e.g. Windows, Mac OS X). However, since all of the typical monolithic services run in kernel-mode in these operating systems, there is little merit to qualify them other then monolithic kernels.

Many operating systems and kernel experts have dismissed the label as meaningless, and just marketing. Linus Torvalds said of this issue:

“As to the whole ‘hybrid kernel’ thing - it’s just marketing. It’s ‘oh, those microkernels had good PR, how can we try to get good PR for our working kernel? Oh, I know, let’s use a cool name and try to imply that it has all the PR advantages that that other system has’.”

Address space¶

The address space term is an overload term that can have different meanings in different contexts.

The physical address space refers to the way the RAM and device memories are visible on the memory bus. For example, on 32bit Intel architecture, it is common to have the RAM mapped into the lower physical address space while the graphics card memory is mapped high in the physical address space.

The virtual address space (or sometimes just address space) refers to the way the CPU sees the memory when the virtual memory module is activated (sometime called protected mode or paging enabled). The kernel is responsible of setting up a mapping that creates a virtual address space in which areas of this space are mapped to certain physical memory areas.

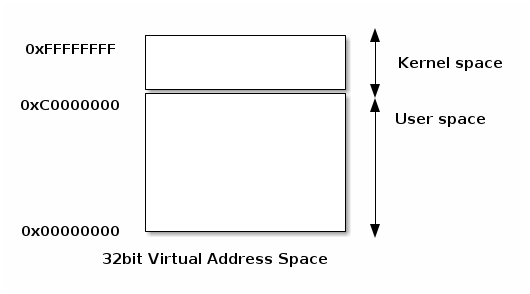

Related to the virtual address space there are two other terms that are often used: process (address) space and kernel (address) space.

The process space is (part of) the virtual address space associated with a process. It is the “memory view” of processes. It is a continuous area that starts at zero. Where the process’s address space ends depends on the implementation and architecture.

The kernel space is the “memory view” of the code that runs in kernel mode.

User and kernel sharing the virtual address space¶

A typical implementation for user and kernel spaces is one where the virtual address space is shared between user processes and the kernel.

In this case kernel space is located at the top of the address space, while user space at the bottom. In order to prevent the user processes from accessing kernel space, the kernel creates mappings that prevent access to the kernel space from user mode.

Execution contexts¶

One of the most important jobs of the kernel is to service interrupts and to service them efficiently. This is so important that a special execution context is associated with it.

The kernel executes in interrupt context when it runs as a result of an interrupt. This includes the interrupt handler, but it is not limited to it, there are other special (software) constructs that run in interrupt mode.

Code running in interrupt context always runs in kernel mode and there are certain limitations that the kernel programmer has to be aware of (e.g. not calling blocking functions or accessing user space).

Opposed to interrupt context there is process context. Code that runs in process context can do so in user mode (executing application code) or in kernel mode (executing a system call).

Multi-tasking¶

Multitasking is the ability of the operating system to “simultaneously” execute multiple programs. It does so by quickly switching between running processes.

Cooperative multitasking requires the programs to cooperate to achieve multitasking. A program will run and relinquish CPU control back to the OS, which will then schedule another program.

With preemptive multitasking the kernel will enforce strict limits for each process, so that all processes have a fair chance of running. Each process is allowed to run a time slice (e.g. 100ms) after which, if it is still running, it is forcefully preempted and another task is scheduled.

Preemptive kernel¶

Preemptive multitasking and preemptive kernels are different terms.

A kernel is preemptive if a process can be preempted while running in kernel mode.

However, note that non-preemptive kernels may support preemptive multitasking.

Pageable kernel memory¶

A kernel supports pageable kernel memory if parts of kernel memory (code, data, stack or dynamically allocated memory) can be swapped to disk.

Kernel stack¶

Each process has a kernel stack that is used to maintain the function call chain and local variables state while it is executing in kernel mode, as a result of a system call.

The kernel stack is small (4KB - 12 KB) so the kernel developer has to avoid allocating large structures on stack or recursive calls that are not properly bounded.

Portability¶

In order to increase portability across various architectures and hardware configurations, modern kernels are organized as follows at the top level:

- Architecture and machine specific code (C & ASM)

- Independent architecture code (C):

- kernel core (further split in multiple subsystems)

- device drivers

This makes it easier to reuse code as much as possible between different architectures and machine configurations.

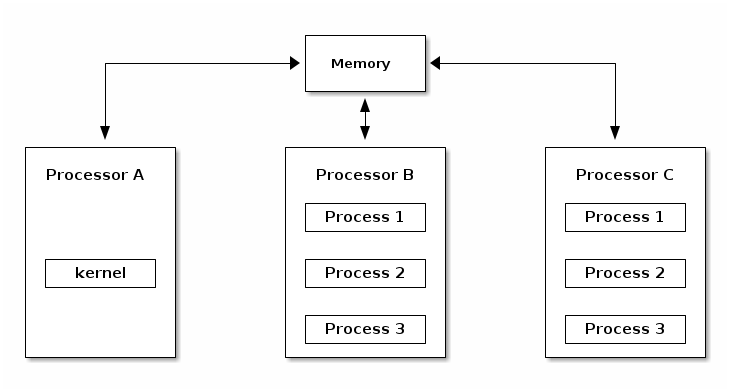

Asymmetric MultiProcessing (ASMP)¶

Asymmetric MultiProcessing (ASMP) is a way of supporting multiple processors (cores) by a kernel, where a processor is dedicated to the kernel and all other processors run user space programs.

The disadvantage of this approach is that the kernel throughput (e.g. system calls, interrupt handling, etc.) does not scale with the number of processors and hence typical processes frequently use system calls. The scalability of the approach is limited to very specific systems (e.g. scientific applications).

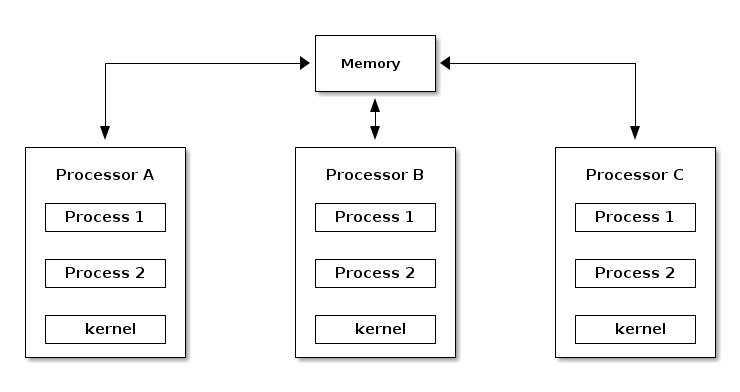

Symmetric MultiProcessing (SMP)¶

As opposed to ASMP, in SMP mode the kernel can run on any of the existing processors, just as user processes. This approach is more difficult to implement, because it creates race conditions in the kernel if two processes run kernel functions that access the same memory locations.

In order to support SMP the kernel must implement synchronization primitives (e.g. spin locks) to guarantee that only one processor is executing a critical section.

CPU Scalability¶

CPU scalability refers to how well the performance scales with the number of cores. There are a few things that the kernel developer should keep in mind with regard to CPU scalability:

- Use lock free algorithms when possible

- Use fine grained locking for high contention areas

- Pay attention to algorithm complexity

Overview the of Linux kernel¶

Linux development model¶

The Linux kernel is one the largest open source projects in the world with thousands of developers contributing code and millions of lines of code changed for each release.

It is distributed under the GPLv2 license, which simply put, requires that any modification of the kernel done on software that is shipped to customer should be made available to them (the customers), although in practice most companies make the source code publicly available.

There are many companies (often competing) that contribute code to the Linux kernel as well as people from academia and independent developers.

The current development model is based on doing releases at fixed intervals of time (usually 3 - 4 months). New features are merged into the kernel during a one or two week merge window. After the merge window, a release candidate is done on a weekly basis (rc1, rc2, etc.)

Maintainer hierarchy¶

In order to scale the development process, Linux uses a hierarchical maintainership model:

- Linus Torvalds is the maintainer of the Linux kernel and merges pull requests from subsystem maintainers

- Each subsystem has one or more maintainers that accept patches or pull requests from developers or device driver maintainers

- Each maintainer has its own git tree, e.g.:

- Linux Torvalds: git://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux-2.6.git

- David Miller (networking): git://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/davem/net.git/

- Each subsystem may maintain a -next tree where developers can submit patches for the next merge window

Since the merge window is only a maximum of two weeks, most of the maintainers have a -next tree where they accept new features from developers or maintainers downstream while even when the merge window is closed.

Note that bug fixes are accepted even outside merge window in the maintainer’s tree from where they are periodically pulled by the upstream maintainer regularly, for every release candidate.

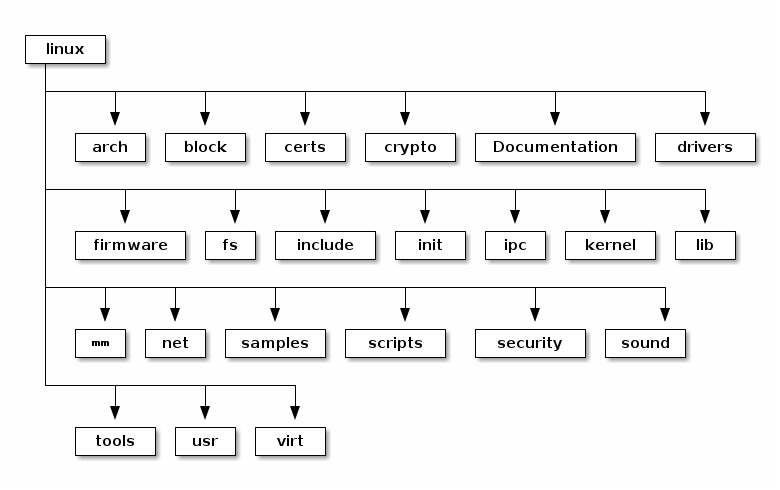

Linux source code layout¶

These are the top level of the Linux source code folders:

- arch - contains architecture specific code; each architecture is implemented in a specific sub-folder (e.g. arm, arm64, x86)

- block - contains the block subsystem code that deals with reading and writing data from block devices: creating block I/O requests, scheduling them (there are several I/O schedulers available), merging requests, and passing them down through the I/O stack to the block device drivers

- certs - implements support for signature checking using certificates

- crypto - software implementation of various cryptography algorithms as well as a framework that allows offloading such algorithms in hardware

- Documentation - documentation for various subsystems, Linux kernel command line options, description for sysfs files and format, device tree bindings (supported device tree nodes and format)

- drivers - driver for various devices as well as the Linux driver model implementation (an abstraction that describes drivers, devices buses and the way they are connected)

- firmware - binary or hex firmware files that are used by various device drivers

- fs - home of the Virtual Filesystem Switch (generic filesystem code) and of various filesystem drivers

- include - header files

- init - the generic (as opposed to architecture specific) initialization code that runs during boot

- ipc - implementation for various Inter Process Communication system calls such as message queue, semaphores, shared memory

- kernel - process management code (including support for kernel thread, workqueues), scheduler, tracing, time management, generic irq code, locking

- lib - various generic functions such as sorting, checksums, compression and decompression, bitmap manipulation, etc.

- mm - memory management code, for both physical and virtual memory, including the page, SL*B and CMA allocators, swapping, virtual memory mapping, process address space manipulation, etc.

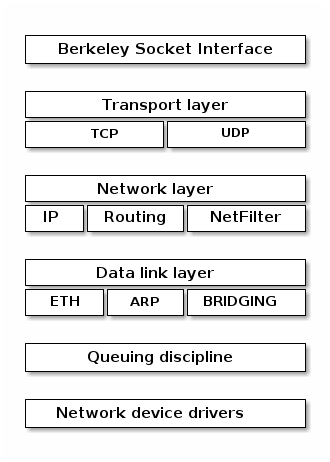

- net - implementation for various network stacks including IPv4 and IPv6; BSD socket implementation, routing, filtering, packet scheduling, bridging, etc.

- samples - various driver samples

- scripts - parts the build system, scripts used for building modules, kconfig the Linux kernel configurator, as well as various other scripts (e.g. checkpatch.pl that checks if a patch is conform with the Linux kernel coding style)

- security - home of the Linux Security Module framework that allows extending the default (Unix) security model as well as implementation for multiple such extensions such as SELinux, smack, apparmor, tomoyo, etc.

- sound - home of ALSA (Advanced Linux Sound System) as well as the old Linux sound framework (OSS)

- tools - various user space tools for testing or interacting with Linux kernel subsystems

- usr - support for embedding an initrd file in the kernel image

- virt - home of the KVM (Kernel Virtual Machine) hypervisor

Linux kernel architecture¶

arch¶

- Architecture specific code

- May be further sub-divided in machine specific code

- Interfacing with the boot loader and architecture specific initialization

- Access to various hardware bits that are architecture or machine specific such as interrupt controller, SMP controllers, BUS controllers, exceptions and interrupt setup, virtual memory handling

- Architecture optimized functions (e.g. memcpy, string operations, etc.)

This part of the Linux kernel contains architecture specific code and may be further sub-divided in machine specific code for certain architectures (e.g. arm).

“Linux was first developed for 32-bit x86-based PCs (386 or higher). These days it also runs on (at least) the Compaq Alpha AXP, Sun SPARC and UltraSPARC, Motorola 68000, PowerPC, PowerPC64, ARM, Hitachi SuperH, IBM S/390, MIPS, HP PA-RISC, Intel IA-64, DEC VAX, AMD x86-64 and CRIS architectures.”

It implements access to various hardware bits that are architecture or machine specific such as interrupt controller, SMP controllers, BUS controllers, exceptions and interrupt setup, virtual memory handling.

It also implements architecture optimized functions (e.g. memcpy, string operations, etc.)

Device drivers¶

The Linux kernel uses a unified device model whose purpose is to maintain internal data structures that reflect the state and structure of the system. Such information includes what devices are present, what is their status, what bus they are attached to, to what driver they are attached, etc. This information is essential for implementing system wide power management, as well as device discovery and dynamic device removal.

Each subsystem has its own specific driver interface that is tailored to the devices it represents in order to make it easier to write correct drivers and to reduce code duplication.

Linux supports one of the most diverse set of device drivers type, some examples are: TTY, serial, SCSI, fileystem, ethernet, USB, framebuffer, input, sound, etc.

Process management¶

Linux implements the standard Unix process management APIs such as fork(), exec(), wait(), as well as standard POSIX threads.

However, Linux processes and threads are implemented particularly

different than other kernels. There are no internal structures

implementing processes or threads, instead there is a struct

task_struct that describe an abstract scheduling unit called task.

A task has pointers to resources, such as address space, file descriptors, IPC ids, etc. The resource pointers for tasks that are part of the same process point to the same resources, while resources of tasks of different processes will point to different resources.

This peculiarity, together with the clone() and unshare() system call allows for implementing new features such as namespaces.

Namespaces are used together with control groups (cgroup) to implement operating system virtualization in Linux.

cgroup is a mechanism to organize processes hierarchically and distribute system resources along the hierarchy in a controlled and configurable manner.

Memory management¶

Linux memory management is a complex subsystem that deals with:

- Management of the physical memory: allocating and freeing memory

- Management of the virtual memory: paging, swapping, demand paging, copy on write

- User services: user address space management (e.g. mmap(), brk(), shared memory)

- Kernel services: SL*B allocators, vmalloc

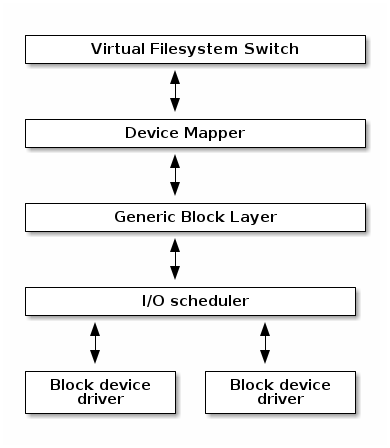

Block I/O management¶

The Linux Block I/O subsystem deals with reading and writing data from or to block devices: creating block I/O requests, transforming block I/O requests (e.g. for software RAID or LVM), merging and sorting the requests and scheduling them via various I/O schedulers to the block device drivers.

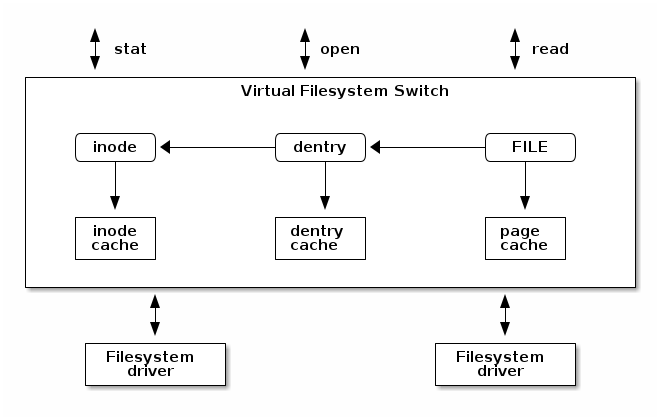

Virtual Filesystem Switch¶

The Linux Virtual Filesystem Switch implements common / generic filesystem code to reduce duplication in filesystem drivers. It introduces certain filesystem abstractions such as:

- inode - describes the file on disk (attributes, location of data blocks on disk)

- dentry - links an inode to a name

- file - describes the properties of an opened file (e.g. file pointer)

- superblock - describes the properties of a formatted filesystem (e.g. number of blocks, block size, location of root directory on disk, encryption, etc.)

The Linux VFS also implements a complex caching mechanism which includes the following:

- the inode cache - caches the file attributes and internal file metadata

- the dentry cache - caches the directory hierarchy of a filesystem

- the page cache - caches file data blocks in memory

Networking stack¶

Linux Security Modules¶

- Hooks to extend the default Linux security model

- Used by several Linux security extensions:

- Security Enhancened Linux

- AppArmor

- Tomoyo

- Smack