SO2 Lecture 08 - Filesystem Management¶

Lecture objectives:¶

- Filesystem abstractions

- Filesystem operations

- Linux VFS

- Overview of Linux I/O Management

Filesystem Abstractions¶

A fileystem is a way to organize files and directories on storage devices such as hard disks, SSDs or flash memory. There are many types of filesystems (e.g. FAT, ext4, btrfs, ntfs) and on one running system we can have multiple instances of the same filesystem type in use.

While filesystems use different data structures to organizing the files, directories, user data and meta (internal) data on storage devices there are a few common abstractions that are used in almost all filesystems:

- superblock

- file

- inode

- dentry

Some of these abstractions are present both on disk and in memory while some are only present in memory.

The superblock abstraction contains information about the filesystem instance such as the block size, the root inode, filesystem size. It is present both on storage and in memory (for caching purposes).

The file abstraction contains information about an opened file such as the current file pointer. It only exists in memory.

The inode is identifying a file on disk. It exists both on storage and in memory (for caching purposes). An inode identifies a file in a unique way and has various properties such as the file size, access rights, file type, etc.

Note

The file name is not a property of the file.

The dentry associates a name with an inode. It exists both on storage and in memory (for caching purposes).

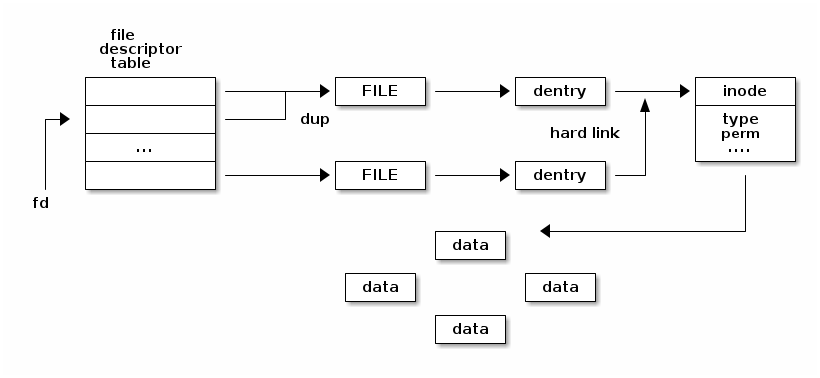

The following diagram shows the relationship between the various filesystem abstractions as they used in memory:

Note that not all of the one to many relationships between the various abstractions are depicted.

Multiple file descriptors can point to the same file because we can

use the dup() system call to duplicate a file descriptor.

Multiple file abstractions can point to the same dentry if we open the same path multiple times.

Multiple dentries can point to the same inode when hard links are used.

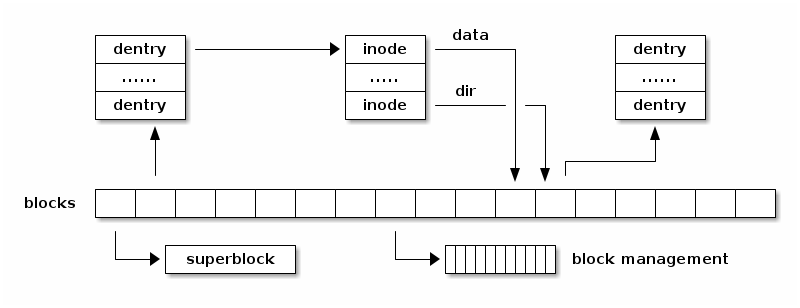

The following diagram shows the relationship of the filesystem abstraction on storage:

The diagram shows that the superblock is typically stored at the beginning of the fileystem and that various blocks are used with different purposes: some to store dentries, some to store inodes and some to store user data blocks. There are also blocks used to manage the available free blocks (e.g. bitmaps for the simple filesystems).

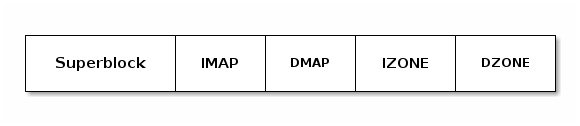

The next diagram show a very simple filesystem where blocks are grouped together by function:

- the superblock contains information about the block size as well as the IMAP, DMAP, IZONE and DZONE areas.

- the IMAP area is comprised of multiple blocks which contains a bitmap for inode allocation; it maintains the allocated/free state for all inodes in the IZONE area

- the DMAP area is comprised of multiple blocks which contains a bitmap for data blocks; it maintains the allocated/free state for all blocks the DZONE area

Filesystem Operations¶

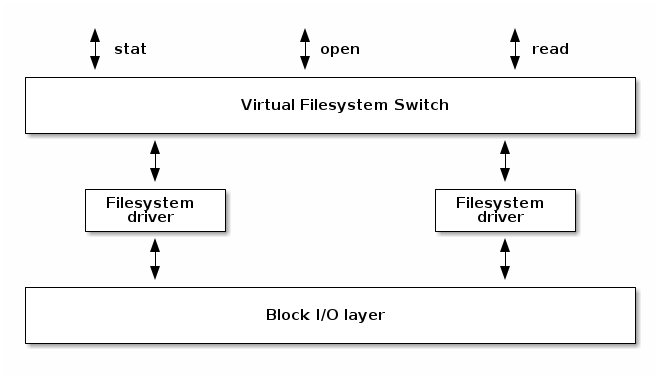

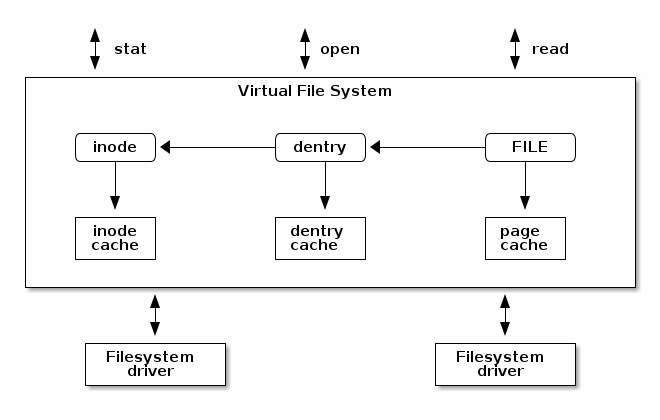

The following diagram shows a high level overview of how the file system drivers interact with the rest of the file system "stack". In order to support multiple filesystem types and instances Linux implements a large and complex subsystem that deals with filesystem management. This is called Virtual File System (or sometimes Virtual File Switch) and it is abbreviated with VFS.

VFS translates the complex file management related system calls to simpler operations that are implemented by the device drivers. These are some of the operations that a file system must implement:

- Mount

- Open a file

- Querying file attributes

- Reading data from a file

- Writing file to a file

- Creating a file

- Deleting a file

The next sections will look in-depth at some of these operations.

Mounting a filesystem¶

A summary of a typical implementation is presented below:

- Input: a storage device (partition)

- Output: dentry pointing to the root directory

- Steps: check device, determine filesystem parameters, locate the root inode

- Example: check magic, determine block size, read the root inode and create dentry

Opening a file¶

A summary of a typical implementation is presented below:

- Input: path

- Output: file descriptor

- Steps:

- Determine the filesystem type

- For each name in the path: lookup parent dentry, load inode, load data, find dentry

- Create a new file that points to the last dentry

- Find a free entry in the file descriptor table and set it to file

Querying file attributes¶

A summary of a typical implementation is presented below:

Reading data from a file¶

A summary of a typical implementation is presented below:

- Input: file descriptor, offset, length

- Output: data

- Steps:

- Access file->dentry->inode

- Determine data blocks

- Copy data blocks to memory

Writing data to a file¶

A summary of a typical implementation is presented below:

- Input: file descriptor, offset, length, data

- Output:

- Steps:

- Allocate one or more data blocks

- Add the allocated blocks to the inode and update file size

- Copy data from userspace to internal buffers and write them to storage

Closing a file¶

A summary of a typical implementation is presented below:

- Input: file descriptor

- Output:

- Steps:

- set the file descriptor entry to NULL

- Decrement file reference counter

- When the counter reaches 0 free file

Directories¶

Directories are special files which contain one or more dentries.

Creating a file¶

A summary of a typical implementation is presented below:

- Input: path

- Output:

- Steps:

- Determine the inode directory

- Read data blocks and find space for a new dentry

- Write back the modified inode directory data blocks

Deleting a file¶

A summary of a typical implementation is presented below:

- Input: path

- Output:

- Steps:

- determine the parent inode

- read parent inode data blocks

- find and erase the dentry (check for links)

- when last file is closed: deallocate data and inode blocks

Linux Virtual File System¶

Although the main purpose for the original introduction of VFS in UNIX kernels was to support multiple filesystem types and instances, a side effect was that it simplified fileystem device driver development since command parts are now implement in the VFS. Almost all of the caching and buffer management is dealt with VFS, leaving just efficient data storage management to the filesystem device driver.

In order to deal with multiple filesystem types, VFS introduced the common filesystem abstractions previously presented. Note that the filesystem driver can also use its own particular fileystem abstractions in memory (e.g. ext4 inode or dentry) and that there might be a different abstraction on storage as well. Thus we may end up with three slightly different filesystem abstractions: one for VFS - always in memory, and two for a particular filesystem - one in memory used by the filesystem driver, and one on storage.

Superblock Operations¶

VFS requires that all filesystem implement a set of "superblock operations".

They deal with initializing, updating and freeing the VFS superblock:

fill_super()- reads the filesystem statistics (e.g. total number of inode, free number of inodes, total number of blocks, free number of blocks)write_super()- updates the superblock information on storage (e.g. updating the number of free inode or data blocks)put_super()- free any data associated with the filsystem instance, called when unmounting a filesystem

The next class of operations are dealing with manipulating fileystem inodes. These operations will receive VFS inodes as parameters but the filesystem driver may use its own inode structures internally and, if so, they will convert in between them as necessary.

A summary of the superblock operations are presented below:

|

|

Inode Operations¶

The next set of operations that VFS calls when interacting with filesystem device drivers are the "inode operations". Non-intuitively these mostly deal with manipulating dentries - looking up a file name, creating, linking and removing files, dealing with symbolic links, creating and removing directories.

This is the list of the most important inode operations:

|

|

The Inode Cache¶

The inode cache is used to avoid reading and writing inodes to and from storage every time we need to read or update them. The cache uses a hash table and inodes are indexed with a hash function which takes as parameters the superblock (of a particular filesystem instance) and the inode number associated with an inode.

inodes are cached until either the filesystem is unmounted, the inode deleted or the system enters a memory pressure state. When this happens the Linux memory management system will (among other things) free inodes from the inode cache based on how often they were accessed.

- Caches inodes into memory to avoid costly storage operations

- An inode is cached until low memory conditions are triggered

- inodes are indexed with a hash table

- The inode hash function takes the superblock and inode number as inputs

The Dentry Cache¶

- State:

- Used – d_inode is valid and the dentry object is in use

- Unused – d_inode is valid but the dentry object is not in use

- Negative – d_inode is not valid; the inode was not yet loaded or the file was erased

- Dentry cache

- List of used dentries (dentry->d_state == used)

- List of the most recent used dentries (sorted by access time)

- Hash table to avoid searching the tree

The Page Cache¶

- Caches file data and not block device data

- Uses the

struct address_spaceto translate file offsets to block offsets - Used for both read / write and mmap

- Uses a radix tree

/**

* struct address_space - Contents of a cacheable, mappable object.

* @host: Owner, either the inode or the block_device.

* @i_pages: Cached pages.

* @gfp_mask: Memory allocation flags to use for allocating pages.

* @i_mmap_writable: Number of VM_SHARED mappings.

* @nr_thps: Number of THPs in the pagecache (non-shmem only).

* @i_mmap: Tree of private and shared mappings.

* @i_mmap_rwsem: Protects @i_mmap and @i_mmap_writable.

* @nrpages: Number of page entries, protected by the i_pages lock.

* @nrexceptional: Shadow or DAX entries, protected by the i_pages lock.

* @writeback_index: Writeback starts here.

* @a_ops: Methods.

* @flags: Error bits and flags (AS_*).

* @wb_err: The most recent error which has occurred.

* @private_lock: For use by the owner of the address_space.

* @private_list: For use by the owner of the address_space.

* @private_data: For use by the owner of the address_space.

*/

struct address_space {

struct inode *host;

struct xarray i_pages;

gfp_t gfp_mask;

atomic_t i_mmap_writable;

#ifdef CONFIG_READ_ONLY_THP_FOR_FS

/* number of thp, only for non-shmem files */

atomic_t nr_thps;

#endif

struct rb_root_cached i_mmap;

struct rw_semaphore i_mmap_rwsem;

unsigned long nrpages;

unsigned long nrexceptional;

pgoff_t writeback_index;

const struct address_space_operations *a_ops;

unsigned long flags;

errseq_t wb_err;

spinlock_t private_lock;

struct list_head private_list;

void *private_data;

} __attribute__((aligned(sizeof(long)))) __randomize_layout;

struct address_space_operations {

int (*writepage)(struct page *page, struct writeback_control *wbc);

int (*readpage)(struct file *, struct page *);

/* Write back some dirty pages from this mapping. */

int (*writepages)(struct address_space *, struct writeback_control *);

/* Set a page dirty. Return true if this dirtied it */

int (*set_page_dirty)(struct page *page);

/*

* Reads in the requested pages. Unlike ->readpage(), this is

* PURELY used for read-ahead!.

*/

int (*readpages)(struct file *filp, struct address_space *mapping,

struct list_head *pages, unsigned nr_pages);

void (*readahead)(struct readahead_control *);

int (*write_begin)(struct file *, struct address_space *mapping,

loff_t pos, unsigned len, unsigned flags,

struct page **pagep, void **fsdata);

int (*write_end)(struct file *, struct address_space *mapping,

loff_t pos, unsigned len, unsigned copied,

struct page *page, void *fsdata);

/* Unfortunately this kludge is needed for FIBMAP. Don't use it */

sector_t (*bmap)(struct address_space *, sector_t);

void (*invalidatepage) (struct page *, unsigned int, unsigned int);

int (*releasepage) (struct page *, gfp_t);

void (*freepage)(struct page *);

ssize_t (*direct_IO)(struct kiocb *, struct iov_iter *iter);

/*

* migrate the contents of a page to the specified target. If

* migrate_mode is MIGRATE_ASYNC, it must not block.

*/

int (*migratepage) (struct address_space *,

struct page *, struct page *, enum migrate_mode);

bool (*isolate_page)(struct page *, isolate_mode_t);

void (*putback_page)(struct page *);

int (*launder_page) (struct page *);

int (*is_partially_uptodate) (struct page *, unsigned long,

unsigned long);

void (*is_dirty_writeback) (struct page *, bool *, bool *);

int (*error_remove_page)(struct address_space *, struct page *);

/* swapfile support */

int (*swap_activate)(struct swap_info_struct *sis, struct file *file,

sector_t *span);

void (*swap_deactivate)(struct file *file);

};

/**

* generic_file_read_iter - generic filesystem read routine

* @iocb: kernel I/O control block

* @iter: destination for the data read

*

* This is the "read_iter()" routine for all filesystems

* that can use the page cache directly.

*

* The IOCB_NOWAIT flag in iocb->ki_flags indicates that -EAGAIN shall

* be returned when no data can be read without waiting for I/O requests

* to complete; it doesn't prevent readahead.

*

* The IOCB_NOIO flag in iocb->ki_flags indicates that no new I/O

* requests shall be made for the read or for readahead. When no data

* can be read, -EAGAIN shall be returned. When readahead would be

* triggered, a partial, possibly empty read shall be returned.

*

* Return:

* * number of bytes copied, even for partial reads

* * negative error code (or 0 if IOCB_NOIO) if nothing was read

*/

ssize_t

generic_file_read_iter(struct kiocb *iocb, struct iov_iter *iter)

/*

* Generic "read page" function for block devices that have the normal

* get_block functionality. This is most of the block device filesystems.

* Reads the page asynchronously --- the unlock_buffer() and

* set/clear_buffer_uptodate() functions propagate buffer state into the

* page struct once IO has completed.

*/

int block_read_full_page(struct page *page, get_block_t *get_block)